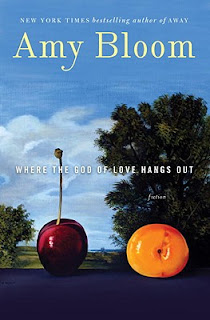

Book Review Where the God of Love Hangs Out By Amy Bloom

Book Review Where the God of Love Hangs Out By Amy Bloom Where The God Of Love Hangs Out, the latest collection from the reliable Amy Bloom, is surprisingly uneven. Perhaps the book relies too heavily on some of Bloom’s favorite tricks. Nearly all its stories are about 98 percent expository setup that seems as though it will never have a point, and then a final 2 percent that creates an absolutely horrifying sense of emotional clarity, of the ways people sometimes damage each other without realizing. Bloom is also fond of taking large leaps through time, then filling in the details in a rush between interconnected stories or sections within the same story. When these techniques fail, the construction becomes too self-evident. But when they work, the stories are deeply devastating jewels. Fortunately, most of God Of Love falls into the latter category, but it’s a closer call than in other Bloom collections.

The biggest problem is how much God Of Love relies on pieces previously published in prior collections. The central quartet of stories—tracing the lives of a mother and her stepson over 30 years—starts off with three of Bloom’s earlier pieces that have been slightly reworked, mostly to make the chronology make sense. The final story in the set has almost too much riding on it, as the family at the stories’ center gathers for one last holiday together, and it can’t live up to the desire for emotional catharsis that the preceding works create.

That said, Bloom specializes in realistic anticlimaxes, and when she does them well, her stories are among the best by anyone working in the form right now. Take “Permafrost,” which is less than 15 pages long, but dances through nearly that many years of history in tracing a social worker’s failed attempts to get her life started, viewed through the prism of her work with a teenager felled by flesh-eating bacteria. Bloom works in lengthy discourses about the fates of polar expeditions in the early 20th century and the complicated histories of two whole families before she’s done, and it all adds up to a final three paragraphs that stun with how deeply they convey a gaping sorrow that can never be filled.

The collection’s opening four stories—tracing the lives of old friends William and Clare, who become lovers, even though they’re married to other people—land among Bloom’s best work. Here, the liberal jumping through time works for Bloom, as she skips years between stories, and her characters are so well-drawn that the desire to find out what happened in the ensuing time is exhilarating rather than enervating. Bloom takes on several points of view—the lovers, their spouses, their children, a disapproving uncle—but she never loses the thread, which is enormously difficult in stories this brief.

William and Clare’s quartet and “Permafrost” are more than enough to recommend Where The God Of Love Hangs Out, especially to those with no prior experience with Bloom, who may find more of value in the central quartet of stories. The other three stories are a mixed bag, but all contain at least one or two paragraphs of evocative writing. Bloom perhaps over-relies on tiny moments that crystallize long-held emotions, which can make her stories feel too self-consciously important and literary. But it can also create exceptional power and beauty.